Centenario del Futurismo

Arte, tecnologia, velocità e innovazione all’inizio del XX secolo

100 Jahre Futurismus

Kunst, Technik, Geschwindigkeit und Innovation zu Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts

International Symposium, Stuttgart, 13-15 May 2009

This was a high-profile meeting organized by the International Centre for Research into Culture and Technology and the Italian Centre of the University of Stuttgart, in cooperation with the State Gallery Stuttgart, the State Academy of Music and the State Academy of Dramatic Arts, Stuttgart, as well as the Istituto Italiano di Cultura Stuttgart.

This was a high-profile meeting organized by the International Centre for Research into Culture and Technology and the Italian Centre of the University of Stuttgart, in cooperation with the State Gallery Stuttgart, the State Academy of Music and the State Academy of Dramatic Arts, Stuttgart, as well as the Istituto Italiano di Cultura Stuttgart.

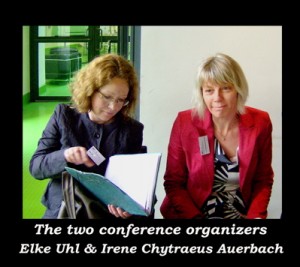

This conference was the only major event in Germany dedicated to the centenary of Futurism. Its driving force and key organizer was Irene Chytraeus-Auerbach, who entered the field of Futurism studies a few years back with a book that compared F.T. Marinetti’s style of public appearances with that of G. D’Annunzio. She is based in Siena and possesses good connections to the world of Futurism scholarship in Italy. This enabled her to line up an impressive array of speakers for this conference, which examined Futurist macchinolatria and tecnofilia from a variety of angles.

Enrico Crispolti as keynote speaker opened the proceedings with a paper that analysed selected examples of images that can be considered paradigmatic for the Futurist technological imagination. He demonstrated that the depiction of speed and dynamism was not at all a Futurist invention; rather, the Futurist painters transformed formal devices that had already been employed by the Divisionists and even Salon painters such as Giovanni Boldini. He also showed that this transformation process was far less uniform than the manifestos suggested.

Matteo D’Ambrosio focussed the conference’s attention on literary aspects and used his semiotic training to position the genre of the manifesto between the poles of poetry and advertisement. Citing the adage of la réclame non è poesia, he showed how Marinetti’s arte di fare manifesti was largely conditioned by pragmatic considerations. He also pointed out that in future we need to analyse the textural matrices of these manifestos and pay more attention to the occasions for which they were written (exhibitions, serate, theatre tours etc.).

Matteo D’Ambrosio focussed the conference’s attention on literary aspects and used his semiotic training to position the genre of the manifesto between the poles of poetry and advertisement. Citing the adage of la réclame non è poesia, he showed how Marinetti’s arte di fare manifesti was largely conditioned by pragmatic considerations. He also pointed out that in future we need to analyse the textural matrices of these manifestos and pay more attention to the occasions for which they were written (exhibitions, serate, theatre tours etc.).

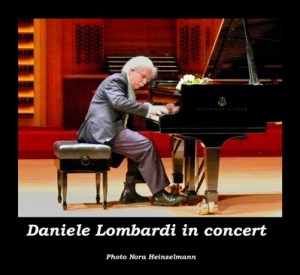

Hansgeorg Schmidt-Bergmann examined in his paper the issues of autogenesis and the construction of non-human mechanical bodies in Marinetti’s Mafarka, whereas Daniele Lombardi presented Luigi Russolo’s collaboration with the artist-engineer Ugo Piatti in the construction and development of his mechanical noise machines (intonarumori). At the end of a fruitful day of presentations and discussions a heated debate ensued in response to Angelo d’Orsi thesis of Futurism’s reactionary ethics and politics.

The second day opened with an excellent paper by Lisa Hanstein on Boccioni’s attempts to sculpt the invisible. This was well-received call for a re-consideration of our understanding of the occult and for more comprehensive research into Futurist art poised between science and para-science. The following papers were dedicated to the performing arts and included a double bill from Günter Berghaus (Bristol) and Henry Daniel (Vancouver). They showed how some of the advanced Futurist experiments with theatre enhanced by the electronic means of radio and television could only find realization in the postwar period, when computers and digital media became available to artists. Also the interactions between mobile stage sets and mechanical actors, first envisaged by Depero and Prampolini, can nowadays find sophisticated realization. This was demonstrated in Daniel’s telematic choreographies that employ motion capture, laser triggers, and a computer-controlled feedback system in order to represent ideas that are rooted in African and Indian spiritualism.

The second day opened with an excellent paper by Lisa Hanstein on Boccioni’s attempts to sculpt the invisible. This was well-received call for a re-consideration of our understanding of the occult and for more comprehensive research into Futurist art poised between science and para-science. The following papers were dedicated to the performing arts and included a double bill from Günter Berghaus (Bristol) and Henry Daniel (Vancouver). They showed how some of the advanced Futurist experiments with theatre enhanced by the electronic means of radio and television could only find realization in the postwar period, when computers and digital media became available to artists. Also the interactions between mobile stage sets and mechanical actors, first envisaged by Depero and Prampolini, can nowadays find sophisticated realization. This was demonstrated in Daniel’s telematic choreographies that employ motion capture, laser triggers, and a computer-controlled feedback system in order to represent ideas that are rooted in African and Indian spiritualism.

The afternoon of the second day was dedicated to architecture and urbanism. Ezio Godoli portrayed the Futurist metropolis as it featured in the utopian imagination of Antonio Sant’Elia and Virgilio Marchi, which was then illustrated in a DVD produced by Vincenzo Capalbo and Art Media Studio in Florence.

The last day was dedicated to the reception of Futurism and Germany. Irene Chytraeus-Auerbach demonstrated in a clear and succinct manner how different the managerial styles could be in the European avant-garde. Herwarth Walden, like F.T. Marinetti, was an extremely able and successful organizer whose network of collaborators covered the whole of Europe. Yet, the ways in which he “performed” his Expressionist mission differed greatly from those of FTM. Mauro Ponzi offered another paper on the reception of Futurism in what he called “the marginal avant-gardes in Germany.” Helmuth Kiesel enlarged on this by focussing on Alfred Döblin and Gottfried Benn’s critical reactions to the Italian movement.

The last day was dedicated to the reception of Futurism and Germany. Irene Chytraeus-Auerbach demonstrated in a clear and succinct manner how different the managerial styles could be in the European avant-garde. Herwarth Walden, like F.T. Marinetti, was an extremely able and successful organizer whose network of collaborators covered the whole of Europe. Yet, the ways in which he “performed” his Expressionist mission differed greatly from those of FTM. Mauro Ponzi offered another paper on the reception of Futurism in what he called “the marginal avant-gardes in Germany.” Helmuth Kiesel enlarged on this by focussing on Alfred Döblin and Gottfried Benn’s critical reactions to the Italian movement.

Apart from the scholarly highlights mentioned here, the Stuttgart symposium featured a high-profile artistic side-programme. Throughout the three days, students from the local Academy of Dramatic Arts intervened with little actions and interactions. Daniele Lombardi gave a concert of Futurist music at the Stuttgart Academy of Music, and the ensemble EXVOCO presented a spectacle of Futurist and Dadaist sound art. The last day was rounded off with a culinary performance. Marco Gast, a local chef who had kept the speakers well-fed during the symposium, offered his interpretation of the Futurist cook book – including an interestingly layered lasagne dish made from algae and gelatined vegetable juices – while thespian and synaesthetic surprises were presented by another group of students from the Academy of Dramatic Arts.

Apart from the scholarly highlights mentioned here, the Stuttgart symposium featured a high-profile artistic side-programme. Throughout the three days, students from the local Academy of Dramatic Arts intervened with little actions and interactions. Daniele Lombardi gave a concert of Futurist music at the Stuttgart Academy of Music, and the ensemble EXVOCO presented a spectacle of Futurist and Dadaist sound art. The last day was rounded off with a culinary performance. Marco Gast, a local chef who had kept the speakers well-fed during the symposium, offered his interpretation of the Futurist cook book – including an interestingly layered lasagne dish made from algae and gelatined vegetable juices – while thespian and synaesthetic surprises were presented by another group of students from the Academy of Dramatic Arts.

Günter Berghaus

One Reply to “Stuttgart Conference: a review by Günter Berghaus”