What’s Left of the Future

an interview with Luca Buvoli

by ItalianFuturism.org’s Jessica Palmieri

JP: Where did you live before studying in Venice at the Academy of Fine Arts?

LB: I was in the US between the age of 3 and 6, and, except for this, I spent the rest of my life in Italy until when I came back to the USA as a 25-year-old.

JP: When were you were first exposed to Futurism? Did you learn about it in your home?

LB: In my family there was barely any knowledge of modern, not to mention contemporary, art. After graduating from a Liceo Scientifico (High School for the Sciences), I spent the summer catching up on Western Art history in order to prepare for the week-long admission exams for the Accademia di Belle Arti in Venice (Academy of Fine Arts). During that time a reproduction of Balla’s La Mano del Violinista caught my eye. My high school art teacher, the artist and musician Toni Vedú, who had previously encouraged my passion for drawing and comic books, reinforced my curiosity for the avant-garde by showing me more images of Futurist works.

JP: What about the Futurist movement attracted you to it?

LB: During most of my time as a student at the Accademia, I competed at an inter-regional level as a mid-distance runner (1500 and 3000 meters). Early in my studies of modern and contemporary art, I was drawn to the representation of speed in futurist works – and for a few months I mimicked their tropes. I then moved on to other interests (expressionism, phenomenology, conceptual art, etc,). Curiously, in those years (early ‘80s) when Futurism was being “rediscovered” in Italy for its innovative forms and actions, there was little public discourse of its complex involvement with Fascism; actually, the then star-teacher at the Accademia (not in my course, though), anti-fascist action-painter Emilio Vedova, was leading his students through the tenets of Futurism for their unavoidable ritual of passage toward gestural abstraction. When I came to the US thanks to a Fulbright scholarship, I discovered that Futurism’s relation with Fascism had instead been the main interpretative channel in an international context. I returned to Futurism years after my superficial mimicry, aware of its contradictions, and with a very different vision of the world.

JP: I understand that you were in Venice at about the same time as the first major Italian show revisiting the subject, Futurismo e Futurismi organized by Pontus Hulten (1986). Did you visit this show, and if so, what was your impression of it? What was the general response to the show by your colleagues?

LB: Like many of my peers, at the time I was struck by the display of hanging props (airplanes, etc.), and by the discovery of so many facets of the avant-garde.

JP: Was there a specific individual or professor who encouraged you or mentored you in your study of Futurism?

LB: Not when I approached it as a mainly visual referent as a student in Italy. Instead, when I began these Meta-Futurist Expositions a few years ago, Claudio Fogu (a scholar at UCSB) suggested quite a few readings that deepened my understanding, and helped me to orient my questions on its myths; allowing me to reinterpret them. Among those who helped me to contact Futurist scholars, or further expanded my research with additional material, I am also thankful to Claire Gilman, Andrea Bellini, Vivien Greene, and Albert Albano. I have been privileged to present and discuss my artworks at symposia with major Futurist scholars at universities such as Harvard and the University of Pennsylvania. Through these discussions I have continued to expand my knowledge in the field, as I continue my creative interpretation of the topics.

JP: You have called your approach to your art “meta-futuristic”. What do you mean when you use this phrase?

LB: By naming my project “Meta-Futurism”, I thought of it etymologically as “Beyond Futurism” as well as “About Futurism”, something that refers to Futurism in a ironic manner. But given my interest in what Pirandello defined “the feeling of the opposite,” I also liked that “meta-futurism” could be seen as the merging of the name of the dynamic avant-garde with the almost concurrent Metaphysical Painting by Giorgio De Chirico, that instead presented anxious and motionless landscapes, perhaps closer to my vision of that specific historical moment. As much as I would have liked to avoid any label, after the broad exposure of my work in the 2007 Venice Biennale, I realized that many visitors needed a concise term to contextualize the work. The idea for the name came soon after I read reviews of my work labeled as “para-futurist”, and “post-futurist”; in a printed interview, the writer even invented a sentence – quoted as if it were said by me – in which I defined my work as “Neo-Futurist”. I realized that if I did not try to name my post-utopian approach to Futurism myself, I had fewer chances to avoid generalization and misunderstanding.

JP: I know that your earlier series Not-a-Superhero deals with similar issues of heroism, idealism and nationalism utilizing a comics format. Have you drawn any correlations between Futurism and comics?

LB: As much as Not-a-Superhero (begun in ’92) was addressing and trying to reroute the construction of masculinity and national identity in the American mythology of the Superhero (from the cold war to the present), in the Meta-Futurist works I attempt to dismantle the construction of the cult of virility, velocity, and violence between the two world wars in Italy.

There are quite a few other parallels that I have been analyzing. Actually, this current Meta-Futurist work is only a small part of a larger project still in progress. It crosses several formats and personalities not only in the comic book and Futurist areas, and I hope to complete and show it in the near future.

JP: The multi-sensory, multi-media nature of your art follows the Futurist program and you have experimented extensively with graphic design and the layout of your catalogs and brochures – were you influenced by Futurist typography and design? What other design elements and styles have influenced you?

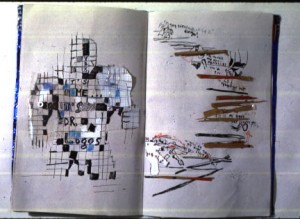

LB: When I begin a new project, and delve into the theoretical research, I explore formats, forms, materials, and contexts associated with the subject matter and content in order to derail or distance them from the original meaning. For more than 15 years I have been engaged with the progressively unfolding structure of the artist’s book/catalog, seen as a large-edition work that shows glimpses of my thought process. In Not-a-Superhero I had enjoyed narrating inside and outside the visual/verbal structure of the comic book; in Flying-Practical Training, a multimedia “Method teaching human unassisted flight” (1997-2005), I worked within the format of technical diagrams and pseudo-scientific text, echoing aerodynamics books and pilot manuals. Since 2002, when I began focusing on flight and WWII, I found myself immersed in the plethora of signs that surrounded the Fascist Regime and its incoherent ideological core. As you know well, advertising and propaganda materials in Italy from the ‘20s to the ‘40s were very inventive languages, and studying them became my next inevitable enterprise.

JP: In what way has your understanding of the Futurist movement evolved as you’ve worked through certain themes in your art?

LB: My recent involvement in Futurism proceeded from the inside out, and backwards. In 1997 I had just begun Flying-Practical Training when my uncle, a decorated WWII pilot, passed away; after the event of September 2001, the Intermediate level of the Method started to reflect on recent and past fears and control in relationship to the activity of flight. In the video Adapting One’s Senses to High Altitude Flying (For Intermediates) – An Almost Silent Version (2004) I combined clips from an interview I conducted with my parents about their early memories of flight and WWII with hand-drawn and computer-generated animation. The recollections of my mother’s subjection to air raids and my father’s memory of imprisonment in camps generated a chain of freely associated words and animated sequences reflecting their inner turmoil. I imbued the dynamic style, colors, and the heroic imagery borrowed from Italian propaganda and advertising from the ‘30s and‘40s, with hesitant language, fading colors, and non-heroic content.

From the source of my immediate family, I expanded my work to the wider perspective of Italians from my parents’ generation. In addition, I was addressing parallels between demagogic strategies used by totalitarian regimes and those utilized today by media-driven societies. I went from using the language of “Secondo Futurismo” and Futurism co-opted by the National Fascist Party, to the memories of Marinetti as recalled by his eldest daughter (A Very Beautiful Day After Tomorrow, 2004-07). The interviews with both Marinetti’s daughters and Futurism scholars for the video documentary How Can This Thing Be Explained? (2004-07), gave me many additional insights on Futurism and its interpretations. As I expanded my knowledge of the period, I was trying to dismantle its rhetoric with several tactics, evoking instead a sense of instability between hope and disillusionment, patriotism and struggle, heroism and betrayal. I then completed my approach to Marinetti’s Manifesto of Futurism (1909): for Velocity Zero (2004-07), I had recorded individuals who have aphasia (speech impediment often caused by brain injury) or stutter reading the Manifesto. Their slowed speech-later transformed into fragmented animated sequences – mirrored the readers’ efforts to fluently capture the text, and their interpretation deflated the Manifesto’s praise of speed and aggression. More recently, in the sculptures Instant Before Incident (2008-09), I focused on the moment preceding the car crash that apparently inspired Marinetti to write the Manifesto.

JP: Luca, you have just had three simultaneous solo shows, one together with Umberto Boccioni in London at the Estorick Collection, one at the Kaaitheather in Brussels, and one in New York at the Susan Inglett Gallery. You have also recently had an article in Modern Painters and a special presentation of your work Velocity Zero on the centennial of the Founding Manifesto of Futurism at the Museum of Modern Art. As your work directly involves a re-imagining of Futurism – making you the man of the hour – do you feel in any way that your art has been superficially appropriated for this anniversary?

LB: Any artistic involvement in a centennial or anniversary is an event that opens art to manipulation, but as the subject matter of my work includes the celebratory rhetoric of images and words, this confrontation is inevitable. I have been lucky that several important curators, directors, and most of the international reviews after the 2007 Venice Biennale and my subsequent shows, have immediately captured the irony and distance in my references to the monumental dreams, and have appreciated some of the tactics I choose to undermine the ideological core of both the historical and present periods I am referring to.

Of course it is impossible to prevent all misunderstanding and manipulations into undesired directions. The major risk would be in Italy, where I am told that some of the current celebrations of Futurism, supported by the right-wing government, hide nostalgic purposes. However I have not been invited to these current Italian manifestations, therefore I don’t have to worry much for the moment. Speaking of appropriation into different contexts, I was very happy that clips of my video with aphasic readers were shown as public service announcements on Italian national television channels (and online) with a message from the Italian Aphasic Association to promote awareness of the condition.

JP: Are you concerned that the issues and imagery you are presenting are seen as “commemorating futurism”, as Peter Schjeldahl has said, or rather, do you feel that you are reinterpreting futurism and contributing to the dialogue as Robert Storr suggests?

LB: Peter Schjeldahl, after describing my works in his review of the 2007 Venice Biennale, also continued his article by writing: “Buvoli’s bottomlessly ironic work does for Italy, in tones of light opera, something like what Anselm Kiefer’s did a quarter century ago, in tones of Wagner, for Germany-bringing to consciousness a historical nexus of aesthetic rapture and political insanity. Stirring the very emotions that he criticizes, Buvoli eschews the starchy condescension of academic political art.”

If to commemorate means to call to remembrance, Mr. Schjeldahl is also aware, like Rob Storr was when he chose my work for the entrance of the Arsenale, of the convoluted paths of memory and the subversive power of paradox.

JP: You have interviewed some of the most important names in Futurist studies. How did you first begin meeting these individuals? Which interview would you say was your most surprising?

LB: The first interview, the one with the scholar Enrico Crispolti, and the ones with the daughters of Marinetti, Vittoria and Luce, were the most memorable. Yet the contacts and recordings with the aphasic and stuttering readers of the Futurist Manifesto were the most surprising, touching, and enriching ones. The most astonishing experience was seeing at the MoMA screenings many patients who had participated in the video and book projects, thrilled and empowered in seeing their speech or writing impediment becoming an agent of awareness and change.

The collection of interviews with Futurism heirs and scholars entitled How Can This Thing Be Explained? (Come si Puó Spiegare Questa Cosa?) is still in progress. I have interviewed almost 20 people who generously shared their extensive knowledge, but there are many more international specialists whose testimonies I would like to collect, in order to produce a few more phases out of this rich and multi-faceted dialog. I am currently looking into funding and co-production with universities that would facilitate the continuation and the distribution of this documentary.

JP: Instant before Incident was on view at the Susan Inglett Gallery in February-March 2009, mirroring your work at the Mattress Factory this past fall in Pittsburgh. In what way do you approach the subjects of velocity and, perhaps more subtly, masculinity is this work?

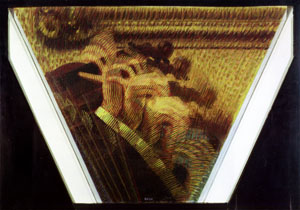

LB: I have adopted several tactics in representing movement, while attempting to slow it down. The oxymoron has always been generative in my work. In Instant Before Incident, Marinetti’s 1908 Fiat is condensed as a trope of representation of velocity; the old car is stretched, squashed, and extended like a cartoon character, yet is constituted by delay. Cars intersect and overlap using a cubo-futurist syntax, which – in its latest version shown at Susan Inglett Gallery – is expanded by the use of an exaggerated perspective. The car that faces the viewer when entering the gallery (almost the size of an actual car) originates in the back of the room as a small car jumping off a ramp. The fluidity of speed is immediately slowed down by porous, wrinkled, and irregular fiberglass panels that oppose the conventional smooth finish of cars.

The related video Ave Machina (2008) intertwines a “psychoanalysis of the car” by scholars Jeffrey Schnapp and Christine Poggi, discussing Marinetti’s Drive (the subtitle of the large sculpture at the Mattress Factory) but more in general masculine drive; it was done intertwining to the interviews some archival footage of races and a car jumping, with new animated sequences and a soundtrack in which Dale Sherrard and I recreated Schubert’s Ave Maria with sounds of classic motorcars.

JP: What projects do you have on the horizon?

LB: Besides some exhibitions in galleries and museums (including a small presence at the Guggenheim), I should soon complete the development of: a virtual Meta-Futurist Mausoleum in collaboration the Stanford Humanities Lab; an animated mini-series expanding on Not-a-Superhero, for a larger web audience; and a multimedia work for Performa in New York this fall. At the same time, I have also been working on a new project in collaboration with NASA scientists that should be shown in US Museums starting from the fall 2010.

JP: Thank you, Luca – we are definitely looking forward to seeing these interesting projects soon!

Luca Buvoli’s Official Website

© Luca Buvoli & Jessica Palmieri, 2009

One Reply to “What’s Left of the Future: an interview with Luca Buvoli”